Living life, painting life – an interview with Larry Madrigal

by Julia Bachmann

Your first solo exhibition Scattered Daydream was recently shown at the Nicodim Gallery in Los Angeles, at a time when we are all still affected by Corona. In the paintings we see a kitchen, a living room and a bed. Do you make this connection between the scenes in your paintings and the scenes that are all too familiar to us at the moment?

Before the pandemic, I was already focused on intimate and quotidian imagery that spoke to other aspects of the human endeavor, from my own perspective. The pandemic only intensified this focus when I began working from home and found myself overly saturated with the subject, so much so that it became almost unbearable at times. There was no escapism. For example, I would walk over from my kitchen to my studio, and make a painting of myself in the kitchen. You see, there was no way out. This particular moment only enhanced my contemplation over the nature of our daily rhythms. I think the cycles of cleaning, eating, sleeping, working, and playing contain timeless secrets.

Your paintings show, in great detail, what seem to be unmentionable situations. Situations that are not commonly talked about because they are considered either too embarrassing, too tedious, or just a part of daily life to which nobody usually alludes. When did you find yourself first drawn to these types of situations?

As an incoming MFA student in 2017, I was determined to make work with some cultural or political commentary given the social polarization of the nation at the time. Many artists can testify about academia’s role in ushering painters into thinking about their work in these social and political terms, as they are expected to defend their ideas within a specific lens.

The big shift for me happened when my daughter was born just two weeks before the MFA program. The urgency of daily responsibilities gradually turned my attention away from the critical and into my own internal struggles. Questions about the meaning of being a father, student, husband, and painter took hold of me. It forced me to pay more attention to quotidian moments and think more creatively about them. It also helped me maintain a healthy distance from the ‘contemporary discourse’ which, in my opinion, can dilute an artist’s true inner impulse in exchange for the currently approved justifications for figurative representation. So, I carefully thought about not thinking, and really tried to not try. I started depicting instances of seemingly inconsequential imagery and infused those moments with the spiritual and psychological.

"I think individuals are simultaneously unique and not unique. So, although people may not relate to specific interiors or figures in these paintings, there may be an abstract association with the idea of responsibility, of fear, of insecurity, of love, of family, and so on."

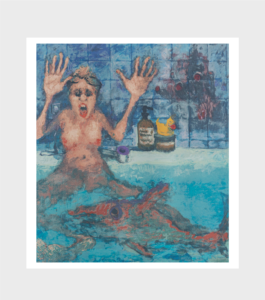

DIRTY MIRROR

Silkscreen print, 37.2 x 29.5 in (94.5 x 75 cm)

Produced on 300 g 100 % cotton Canson paper

The paintings seem to show your point of view: situations you experienced but that most people can relate to: we all go down the street to buy groceries; once in a while we buy new clothes; and we might look at ourselves in a mirror that we are cleaning. Do your paintings tell a story for everyone or do they tell your story specifically, whether others might relate to it or not?

Relatability is a byproduct of making what feels most honest. I think individuals are simultaneously unique and not unique. So, although people may not relate to specific interiors or figures in these paintings, there may be an abstract association with the idea of responsibility, of fear, of insecurity, of love, of family, and so on. For example, when a comedian tells a successful joke, we don’t laugh because we remember the exact situation specifically. Instead we laugh because we understand the essence of the premise and condition presented. I like the challenge of making very personal work transcend my individuality, and I find that being as honest as possible is one big step in that direction.

Do you ever cheat yourself into another role through your paintings — in order to tell a story that you haven’t actually experienced yourself?

The short answer is no. But, I do allow other stories to enter my work through a kind of periphery as I come across new and different things. Instead of making myself a protagonist, I try to be honest with my reactions to things. I don’t think we ever truly understand otherness of any kind, all we can do is respond to it. The response can say a lot about our attitude towards other stories. So I’m not really concerned with accurately representing a moment. As a painter, all I can do is respond to life with honesty and transparency.

Sometimes there’s a lot going on in your paintings; sometimes there’s a quietness in them, as in good morning. Sometimes we find both those elements in one scene. Besides the objects in your paintings (i.e. books, dolls, gadgets) and the story they might tell, it’s also about how the protagonists react to what is in the painting.

This is one of the most exciting things about narrative painting to me. Nothing in the work is neutral. Everything is associational. As I work to build these images, there are times when I become extremely sensitive to the ‘objects’ depicted. They can become witnesses or characters in the unfolding of a story. The rhythm, proximity, and articulation of moments all work together to support an intangible feeling. For example, a child is usually associated with innocence, therefore, if that innocence is juxtaposed with taboo, it can cause an interesting reaction. I feel like a scientist pouring different imagistic symbols in a test tube to see what happens. This of course has its own pitfalls, as a narrative painting can become overly obvious or saturated with cliché. So I try to be more nuanced about it.

In a way, the openness and humour in your work uncovers the seriousness of the situations. You let people into these hidden, personal zones and tell stories others probably would prefer to forget than have captured on a canvas.

Going back to the idea of representation, subject matter is either immediately expected or scrutinized when painting figuratively. During grad school, I was wrestling with what makes a painting seem important, or what it means to make an important painting. I tried to go the opposite way and depict the most non-important scenarios. I quickly realized how important those moments really are. Hollywood would never depict a superhero doing laundry or cutting toenails (laughs). But it is those moments that say a lot about us. I believe behind closed doors, we are a lot more similar than we assume. But only those closest to us get to see our weaknesses. So I realized that love is the only place where I can allow myself to be simultaneously pathetic and assured. In a way, my paintings are really about love.

You told me about the painting that hung on the wall in your grandmother’s house which subconsciously moved you to become a painter. Do you see your paintings and your prints hanging in the rooms of others, influencing their lives?

The funny thing is that I always assumed these paintings would be with me forever. Now that they are making their way across the country and abroad, I am interested to see how their new life will be. Wherever they are, they are a real part of my soul and I hope they add something special to either a home or collection. If there is any influence from my work, I hope it’s in the mere sense of love for the drama of life.