Eva Beresin-Perceptions of my body

From the beginning, your life has been surrounded by art, influenced by your father's collection and the drawings you created on Sundays at the famous Gerbeaud cafe in Budapest. What was the first subject that inspired you to paint?

My first subject inspiration was born from seeing my parents sitting together at the coffee house with friends, most of them also holocaust survivors. After the Second World War they returned and lived in Budapest for ten to fifteen years, started a new family life, and hoped for a better world. I got fascinated by their friend´s faces, as well as the tormented expressions of aged solitaire women and the characters that cover the pain under the thick make up and red lips. Observing this truly impressed me and I decided to represent these bizarre looks from my childish slightly naive perspective.

During your studies at the School of Visual Arts in Budapest, you had your own atelier and refined the technique of composition. How would you describe these first years of learning and developing?

The best thing that school gave me is the basic knowledge of art history, understanding of geometry, perspectives, nude drawing and the regular exercise of portraying humans and animals. Although it was my father who taught me how to see and love art, long before the school, there was one teacher who I remember to be an additional influence. My room at home was also my studio, the table was full of pencils and paints, to later become my easel too. There was constantly something going on. I experimented a lot during that time.

I realized how much my family history influenced my life. Being aware of where you come from gives you a solid foundation to understand and tell your story.

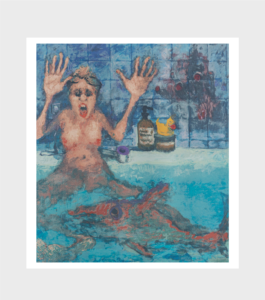

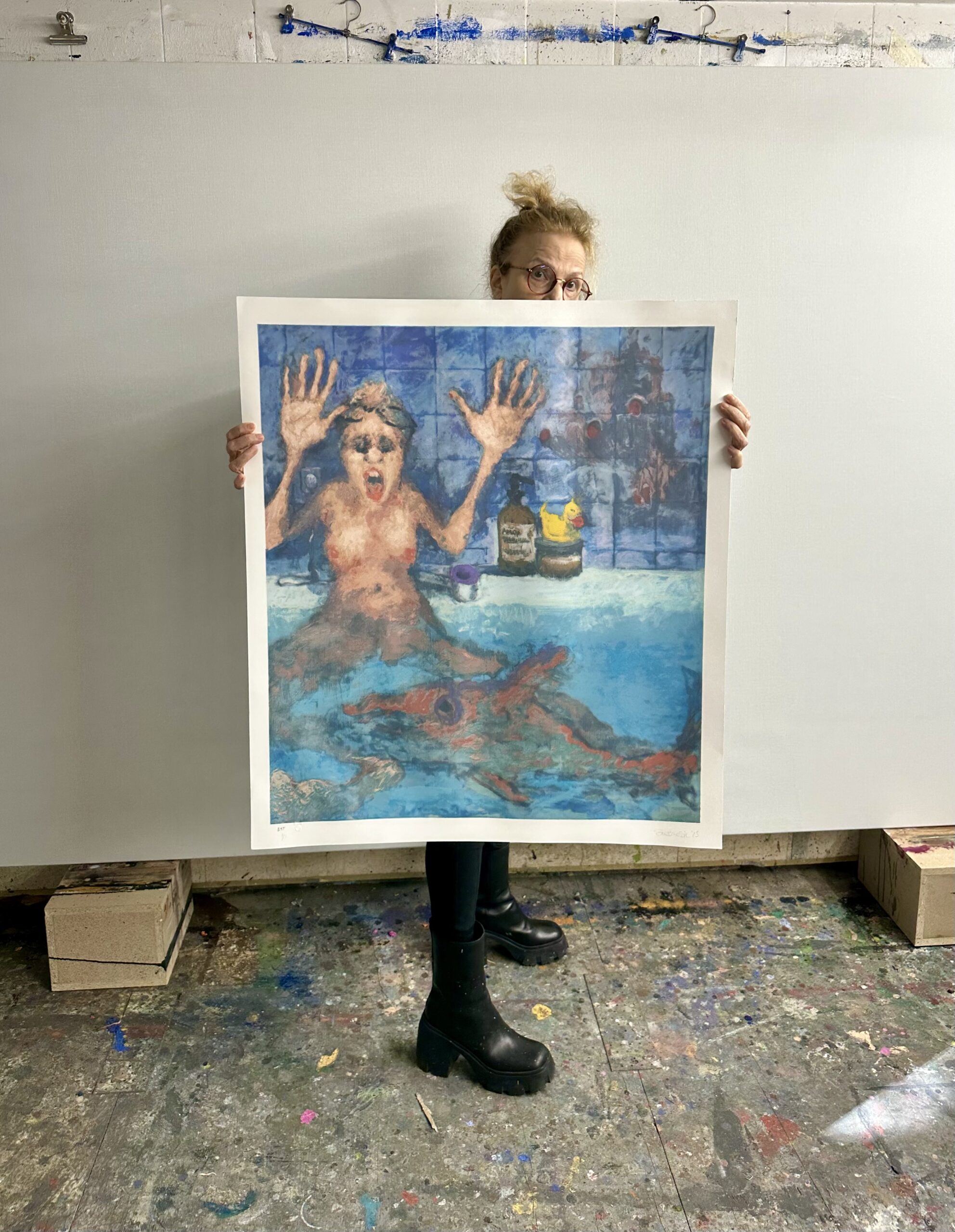

Fear of Deep Conversations

Silkscreen print, 33.8 x 29.9 in (86 x 76 cm)

Produced on Somerset Satin 300g

In the 70s, the ideology and aesthetics of socialist realism still prevailed as an official method of creation within the artistic education of the countries of Eastern Europe. Did this political-social situation condition your work in this period?

The established artists were completely conditioned by the system and the aesthetic of socialist realism. As a child and later as a young student, I had the opportunity to experiment within a “free” environment, with the condition that the resulting work could not be shown or shared outdoors.

The art world is made-up of various systems that contribute, or not, to the development of an artist's career and the visibility of the work. In your case, how did you “get through the door” to international recognition and why do you think it didn't happen a little earlier, for example, after you graduated?

I finished art school at the age of 19 and moved to Vienna shortly after. It took me a while to adjust to the environment before I started painting again. This has always been my biggest passion, but I never dared to imagine how I could make a living from my work as an artist, and somehow, I did. Also, I never had enough confidence in myself to contact a gallery. For years I was organizing my own exhibitions in private spaces that I rented for short periods of time. It wasn’t until 2014 that Charim Galerie in Vienna asked me to do a project together. During that time, I started to show a small selection of my work on Instagram. It was something very new for me and I felt special about the use of this form of visibility: a platform where you can present yourself to the world and they look at you. That was how Kenny Schachter saw my work; his writing and continued interest opened the door to international recognition and beyond.

In 2015 you held a comprehensive personal exhibition at the Charim gallery, in Vienna, entitled My Mother's Diary: Ninety-Eight Pages, based on your mother's diary after her release from Auschwitz. Do you consider yourself an interpreter of your family history? Was the production process of this show a way to connect with the past and heal?

I think the translation of my mother’s diary changed everything. During the completion of this project, I realized how much my life was influenced by my family’s history and how little I knew about it until then. Everything that was previously suppressed suddenly became clear. Being aware of where you come from gives you a solid foundation to understand and tell your story.

Although you use photo references to create, you do not copy them directly or make sketches. How do you manage creative freedom during the process and what are the limits you challenge?

Sketching is not for me, I think there is a lot of one personality that must go on the canvas, and I am hyper, spontaneous, and impatient. I always start with a face and work around it without knowing what I will do. I love the freedom of my process and the surprise of how it will end up looking. It is easier to throw something on the canvas and start reacting and building it as I go. Otherwise, I can’t do it. But also, the rawness and the first strokes are always my best work. That’s what makes my work fresh and full of character.

Beside painting, you also draw and use various media such as 3D. Do you recognize yourself as an artist in favor of technology and cross-functionality or do you feel more comfortable with traditional methods of creation?

I definitely love trying new technologies, possibilities, mixing materials and seeing what will happen.

In your work you depict faces, creatures and scenes impregnated with symbolism, tragedy and humor, able to transform pain into an intimate and positive moment at the same time. Is this a recurrent statement in your artist-life philosophy?

I don’t know if this is an artist’s life philosophy but I am convinced that the key to surviving tragedy is humor and for me the only way to handle pain is through cynicism.

An organic way to shape the memory is through multidisciplinary projects that involve art, architecture, design and fashion. Do you think your work embraces multifunctionality?

I am very interested in multifunctionality. All those disciplines you specified are deeply rooted in the creative practice of interconnectivity and constant exchange between them. They have always been influenced by economic, political and cultural development for centuries.

How is a typical day like in your studio while you paint?

I work every day, usually from afternoon to night for a few hours, but I really work hard when I have a deadline. Stress is fuel for me. I am always full of energy and creativity, but doubts can also arise.

Your work has been incorporated in important international art collections, including the Albertina Museum in Vienna and the Roux Collection. Could you share more details on the latest collaboration with Multiplo?

It is an honor to be part of the Roux Collection. I strongly sympathize with Multiplo’s interest in the accessibility of art. Johnny Roux’s method of collecting art is admirable.